Fable was first launched in a world where LGBTQ+ representation was still in its infancy. Civil partnerships weren’t yet legal in the UK, let alone gay marriage, and wider acknowledgement and support for transgender people was virtually non-existent, the virtriol of the current climate repalced with ignorance and apathy. I was in primary school when Lionhead’s Fable arrived in 2004, an ambitious RPG that approached the concept of player morality in an RPG like few games before it ever had, especially in the mainstream console space.

It was a groundbreaking experience, although it was also yet another victim of Peter Molyneux’s perpetual habit of broken promises and needless overhype that painted games as something they’d never be capable of being. You couldn’t plant a tree and watch it grow throughout the course of the campaign, but you could choose to make a whole town to fall in love with you or instead murder them in cold blood. Much like the studio’s previous efforts, the definition of good and evil in Fable was laughably black and white. This didn’t change much with future games, which would continue to usher you down a duo of paths that would lead to the same conclusion with only a few notable consequences setting them apart.

Related: What To Watch, Read, And Play Now The Owl House Is On Hiatus

But I’m not here to talk about Fable’s morality system – instead, I want to touch on the unique place it occupied in the queer zeitgeist back in 2004 and how, in many ways, it was ahead of its time. Fable is a game that isn’t afraid to show that men can be attracted to our male hero, and your character can flirt with fellow boys, shower them with gifts, or even offer their hand in marriage instead of opting for a traditional heteronormative relationship. It was a bold step forward at the time, yet in retrospect is still lined with a surrounding homophobia that is damaging to the progression it is trying so desperately to claim as its own. Having replayed the entire game earlier this month, it left a bad taste in my mouth.

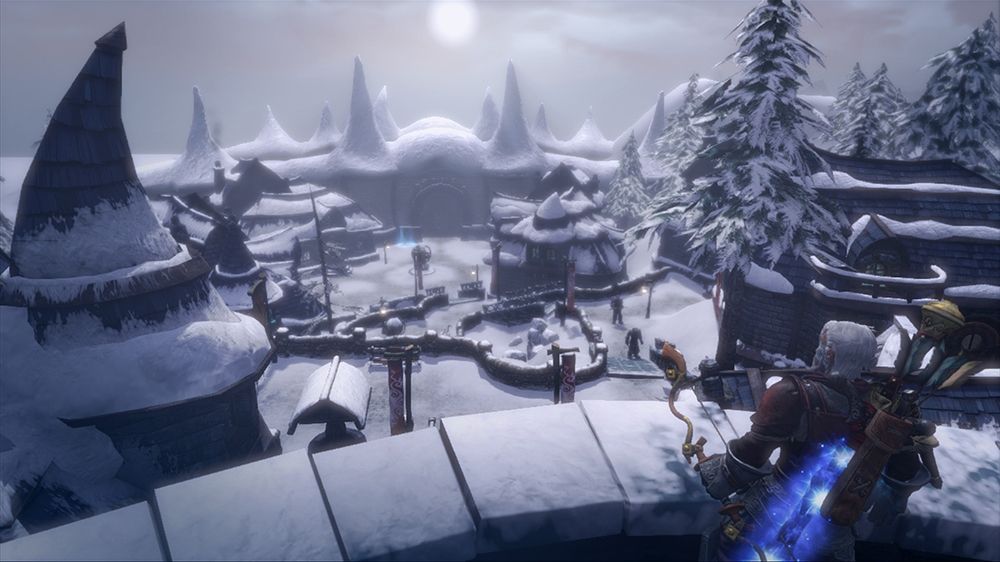

Men in Fable are old-fashioned, many of them bald, working class villagers who walk about towns like Bowerstone and Oakvale spouting a generic selection of lines as they toil away in the working hours before retiring to the local pub in the evening. They voted Leave, basically. They’ll moan about their spouses and shower praise upon me as I pass through town, and if one of them tickles my fancy, I can spoil them with chocolates and perfume until they’re down to get hitched. I’m pretty sure that’s how real romance works, right? Unlike the straight relationships in Fable, which often feel like they’re coming from the heart, gay romances appear to be viewed from a farcical perspective.

When the idea of marriage between two men is brought up, NPCs will often refer to you “as just a couple of blokes being blokes” and how the concept of genuine love between two people of the same-sex is viewed as a joke, or lacks the legitimacy of its straight counterparts. I saw it as a joke when I first played Fable as a child, but now it just feels hurtful and outdated, like Lionhead added such inclusivity purely to paint it as a joke for its audience that likely consisted of white, straight men. Girls couldn’t play games back in 2004, I’m fairly sure it was illegal. I suppose when society itself wasn’t accepting of gay marriage upon the game’s initial arrival, a respectful portrayal of such concepts weren’t on the minds of a development team who were trying to create a world that felt both faithful and fantastical.

It’s an unfortunate product of its time, and the respect I feel for Fable’s willingness to encourage discussion around LGBTQ+ issues is diluted by a portrayal that feels achingly heteronormative. Gay men in reality aren’t always making jokes about how they’re bumming all of the time and are just a couple of blokes on the banter train. Queer communities can make these jokes about themselves, but it comes with a deeper acknowledgement that they are people too who deserve love, respect, and rights like everyone else. They didn’t have that in 2004, and other media in the UK at the time was a stark representation of that.

Little Britain was still airing at the time, which is a painfully bigoted show that openly mocks gay men, transgender women, and pretty much everyone who wasn’t a white guy. Though Little Britain stars and writers Matt Lucas is gay and David Walliams, though he often keeps his private life away from public view, has discussed having relationships with men, the jokes feel like punching down rather than winking at stereotypes as cutting satire.

Lucas and Walliams have since said they regret doing Little Britain, but given it made the careers of both men I imagine they wouldn’t be where they are now without it. The show fed off the accepted prejudice of minority groups for cheap laughs and crass humour, knowing its audience were eager to overlook their own bigotry in favour of laughing at those less fortunate than they are. Emily Howard, Walliams’ ‘laydee’ character, likely screwed with a younger version of me who had yet to see trans women in the media who truly represented me. If I had, perhaps I’d be a lot happier today than I actually am.

I’d put Fable in the same ballpark as Little Britain, a game which was happy to poke fun at those different from the average joe for a brief giggle. Another example is how dresses are sold in the game’s shops and you can wear them, but the item descriptions suggest that doing so is an act of abnormality, like you’re going to be made fun of by going against what this fantasy world expects of you. Why? Fable is filled with hobbes, balverines, and ancient magic – but god forbid a bloke wears a dress.

Fable was a problematic step forward for queer representation, and its sequels did a much better job with gay relationships as female playable characters and lesbian relationships allowed for a greater expression of romance that, while still played for laughs, didn’t feel like it was aiming for anything particularly sinister. With a reboot on the horizon, Playground Games will need to recognise the missteps of past games, and how it will need to create a fantasy world that is inclusive, forward thinking, and doesn’t accidentally dip its toes into the pool of old-fashioned bigotry. Keep the classic British tone, but understand the prejudices that such an attitude has long been attached to.

Next: Saints Row Highlights Gaming's Toxic Relationship With Nostalgia