Quentin Tarantino’s Django Unchained is a wildly original movie. It tells a huge, epic, cinematic fairy tale through the lens of a spaghetti western in the context of the ugliest, most challenging chapter of American history. As a rollicking action movie set against the backdrop of slavery, Django Unchained manages to have its cake and eat it, too. It’s a big, fun, entertaining popcorn movie, but it doesn’t shy away from the brutality of its historical context.

Jamie Foxx’s portrayal of an ex-slave who trains to become the fastest gun in the South and goes on a blood-soaked rampage through the plantations of Mississippi is the ultimate historical revenge fantasy. There’s no movie quite like Django Unchained. But, as with all of Tarantino’s other movies, it borrows heavily from previous films.

RELATED: What Separates Spaghetti Westerns From Regular Westerns?

Just as his World War II epic Inglourious Basterds was named after a 1978 Enzo G. Castellari macaroni combat classic (albeit with a misspelled title), Tarantino’s first foray into the spaghetti western borrowed its title – and, by extension, its hero’s name – from Sergio Corbucci’s 1966 masterpiece Django.

Having been inspired by Corbucci and fellow Italian western helmer Sergio Leone throughout his entire career, Tarantino has made pretty much all of his movies spaghetti westerns in one form or another. From the beginning of his directorial career, Tarantino’s recurring graphic violence, kinetic action scenes, and grim tales of revenge have transplanted the tropes and motifs of the spaghetti western into genres like crime films and martial arts actioners. Pulp Fiction is a spaghetti western set in contemporary Los Angeles and Kill Bill is a spaghetti western thrown into a blender with martial arts and blaxploitation movies.

Django Unchained was Tarantino’s first full-on western, the movie that granted Tarantino access into the pantheon of western directors. And even then, it doesn’t take place in the West – it takes place in the Antebellum South – so it’s not even technically a western. But that’s Django Unchained’s greatest strength: it’s a new kind of western.

One of the staples of Hollywood filmmaking since the very beginning, the western is possibly the most well-worn genre in cinema. Its tropes are universally familiar, the subversions on its tropes have since grown stale, and the only way the genre can thrive today – a century after its inception – is with subversions on those subversions. With Django Unchained, Tarantino did the impossible: he came up with a fresh take on the western genre.

Django isn’t the only Sergio Corbucci movie that Tarantino’s film took influence from. The historical revenge fantasy of an ex-slave killing white slavers is a nod to Corbucci’s Navajo Joe, in which a Native American warrior tracks down the white oppressors who slaughtered his tribe. The montage of Dr. Schultz training Django as a gunfighter through the winter is a nod to the bleak, snowy landscapes of Corbucci’s The Great Silence. But, based on the title, it seems safe to say that the movie’s strongest influence was Django.

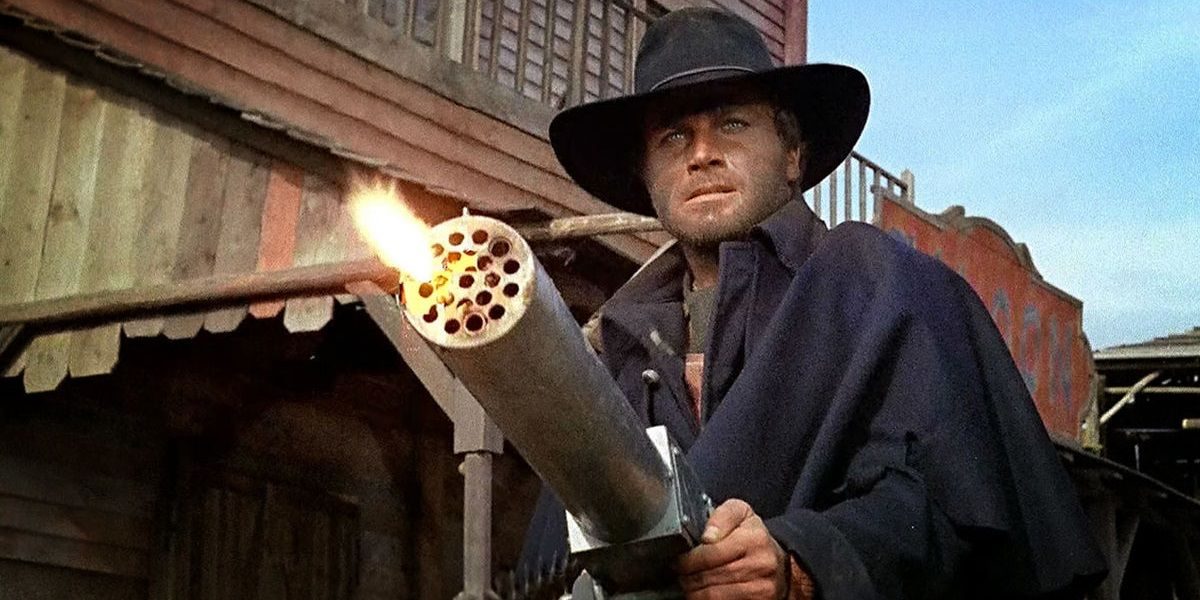

One of the early boundary-pushing masterworks that established the tropes of the spaghetti subgenre, Django is an even more brutal western than the one Tarantino named after it. Django Unchained is not short on shocking violence – a slave is mauled by attack dogs, Django shoots off a tracker’s penis, and every frame in the Candyland shootout is splattered with giallo red – but the original Django’s violence still packs a punch more than 50 years later.

Django Unchained was just the latest in a long line of unofficial Django movies. Audiences were so taken with Franco Nero’s title character in Django that dozens of subsequent filmmakers were inspired to steal his name and use it for their own spaghetti westerns. By borrowing the eponymous hero’s name, Django Unchained joined a massive sub-canon of the spaghetti western that includes Django Shoots First, Kill Django… Kill First, Son of Django, A Few Dollars for Django, Django, Prepare a Coffin – the list goes on. There was only ever one official sequel that Nero returned for, 1987’s Django Strikes Again. Nero does appear in Django Unchained, but not as Django. He plays Amerigo Vessepi in the notorious Mandingo scene. When Foxx’s Django meets Vessepi at the bar, there’s a nod to Nero’s most iconic role as he’s the only one who knows that the D in Django’s name is silent.

Corbucci’s Django isn’t a big, extravagant epic like Tarantino’s Django Unchained. Like Sergio Leone’s own pioneering spaghetti western masterpiece A Fistful of Dollars, Django is a loose reimagining of Akira Kurosawa’s Yojimbo that takes the story out of feudal Japan and places it in a rough, gritty, violent vision of the Old West. But where Fistful is a shot-for-shot remake of Yojimbo in some places, Corbucci’s movie works best when it deviates from the Kurosawa classic.

Franco Nero’s Django drags a mysterious coffin across the frontier, and the reveal of what’s inside is worth the build-up. Nero’s Django has a more personal, relatable vendetta against the villain, too. Whereas Clint Eastwood’s Man with No Name (and Toshiro Mifune’s Sanjuro in Yojimbo) are driven by protecting a town from two warring gangs, Nero’s Django is driven by his desire to avenge the love of his life, Mercedes Zaro. The villain who killed her, Major Jackson, is not quite a white slaver like Calvin Candie in Django Unchained, but he is an ex-Confederate officer, so he did fight for Candie’s right to own slaves.

Django Unchained is, of course, the most overt homage to Corbucci’s Django on Tarantino’s filmography. But it was far from his first reference to the movie. Tarantino borrowed the most shockingly violent scene from Django to create the most shockingly violent scene in his debut feature, Reservoir Dogs. The most talked-about moment from Reservoir Dogs was the torture scene. Mr. Blonde torturing a tied-up police officer for fun prompted walkouts during some screenings.

While the juxtaposition of “Stuck in the Middle with You” against the gruesome on-screen violence was a nod to Alex DeLarge’s rendition of “Singin’ in the Rain” during a home invasion in A Clockwork Orange, the act of severing an ear came from Django. One of Major Jackson’s henchmen cuts off an innocent man’s ear in front of the whole town in Django. Except Corbucci’s movie takes the violence even further than Tarantino’s infamous homage. In Reservoir Dogs, the ear-cutting doesn’t even happen on-screen, because the camera pans away just in time. In Django, not only do we see Jackson’s henchman cutting off the ear; he then forces the man to eat it.

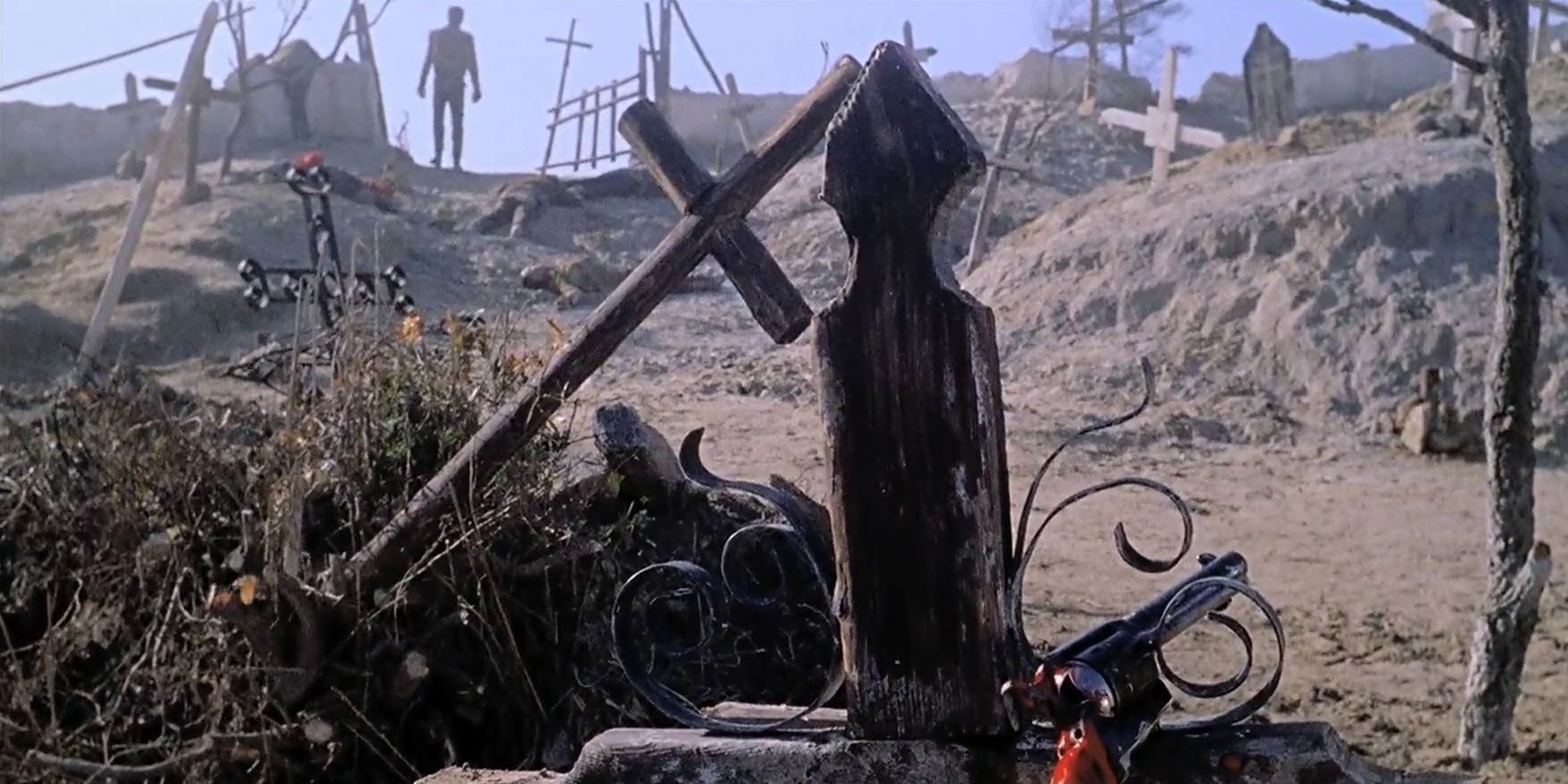

Django culminates in one of the most glorious, spectacular, crowd-pleasing climactic shootouts in the entire western movie canon. The final scene takes place in the cemetery, where Django is resting against Mercedes’ tombstone, waiting for Jackson and his men to arrive for the final standoff. Django’s hands have been crushed by a side villain, so he can barely hold his revolver between his palms, let alone pull the trigger, so he doesn’t have much chance against a band of sadistic gunslingers. He uses his teeth to remove the trigger guard and rests the gun against the tombstone.

When Jackson and his men show up, Django starts yanking back on the hammer with one of his crushed hands and shoving the trigger against the tombstone with the other. There’s something beautifully poetic about Django gunning down the bad guys by pushing the trigger of his gun against the tombstone of the woman he’s avenging. As brutal as Django Unchained is, 1966’s Django remains a high benchmark of brutality for the spaghetti western.

NEXT: Quentin Tarantino Should Finally Tackle One Of These Two Genres In His Final Movie